The first phase of Brexit negotiations focused on three topics: the size of the UK’s so-called divorce bill; the rights of EU citizens living in the UK and UK citizens residing in the EU; and post-Brexit border arrangements on the island of Ireland.

Under the terms of the UK’s withdrawal agreement, the 3.6 million EU citizens living in the UK will have the right to stay.

Although more EU citizens continue to arrive in the UK than the numbers who leave, the level of net migration of EU citizens to the UK is at its lowest since 2009.

The largest decline in EU net migration over the last years has been seen in EU8 citizens – those coming from the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia.

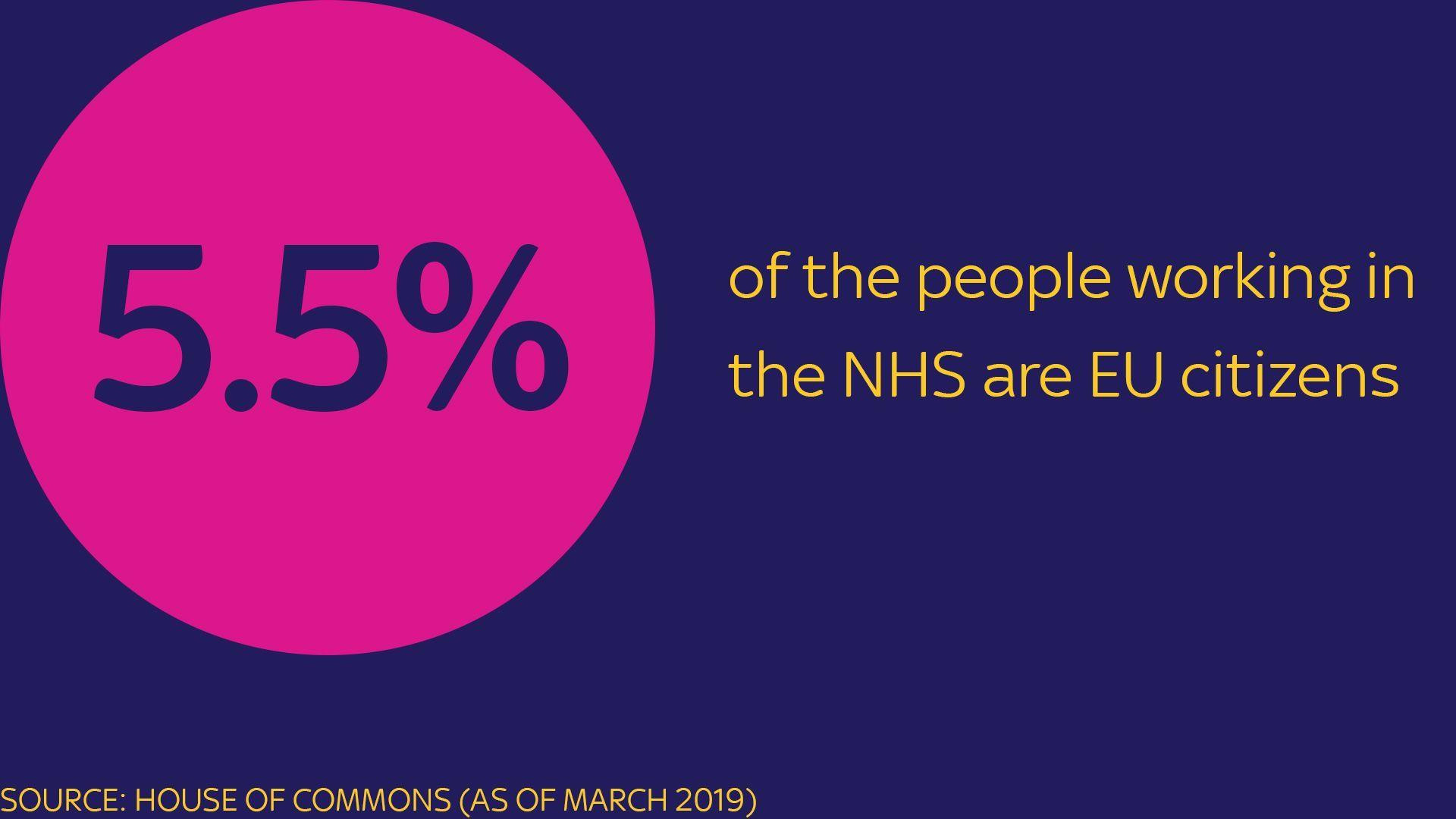

There have been fears of a staffing crisis in the NHS due to the dwindling number of EU nationals coming to the UK in recent years.

Around 65,000 of the total 1.2 million people working for the health service in England are EU nationals.

Doctors’ and nursing unions have expressed concerns about the impact of Brexit on NHS staffing levels.

The UK’s withdrawal agreement also safeguards the right of Britons to stay in those EU countries where they are currently living.

Resignations and political instability caused by uncertainty surrounding when and how the UK would leave the EU had an impact on the economy.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, GDP is 2.5% below what it would have been without Brexit, although other projections estimate this figure at a lesser 1% and consider the slowdown temporary.

Economic growth is one of the factors that affects the level of business investment, and the private sector has been cautious during this period.

Investment has barely grown since 2016. A Bank of England report in November 2019 says total business investment is around 11% lower as a result of Brexit and the slowdown in global growth.

The performance of stock market - in particular the mid-range FTSE 250, which is more domestically focused than the FTSE 100 - also seems to tell a story of lack of confidence in the country’s economy.

Meanwhile, the pound – which fell sharply versus the US dollar on the referendum result, to levels not seen since 1985 – has yet to recover the lost ground.

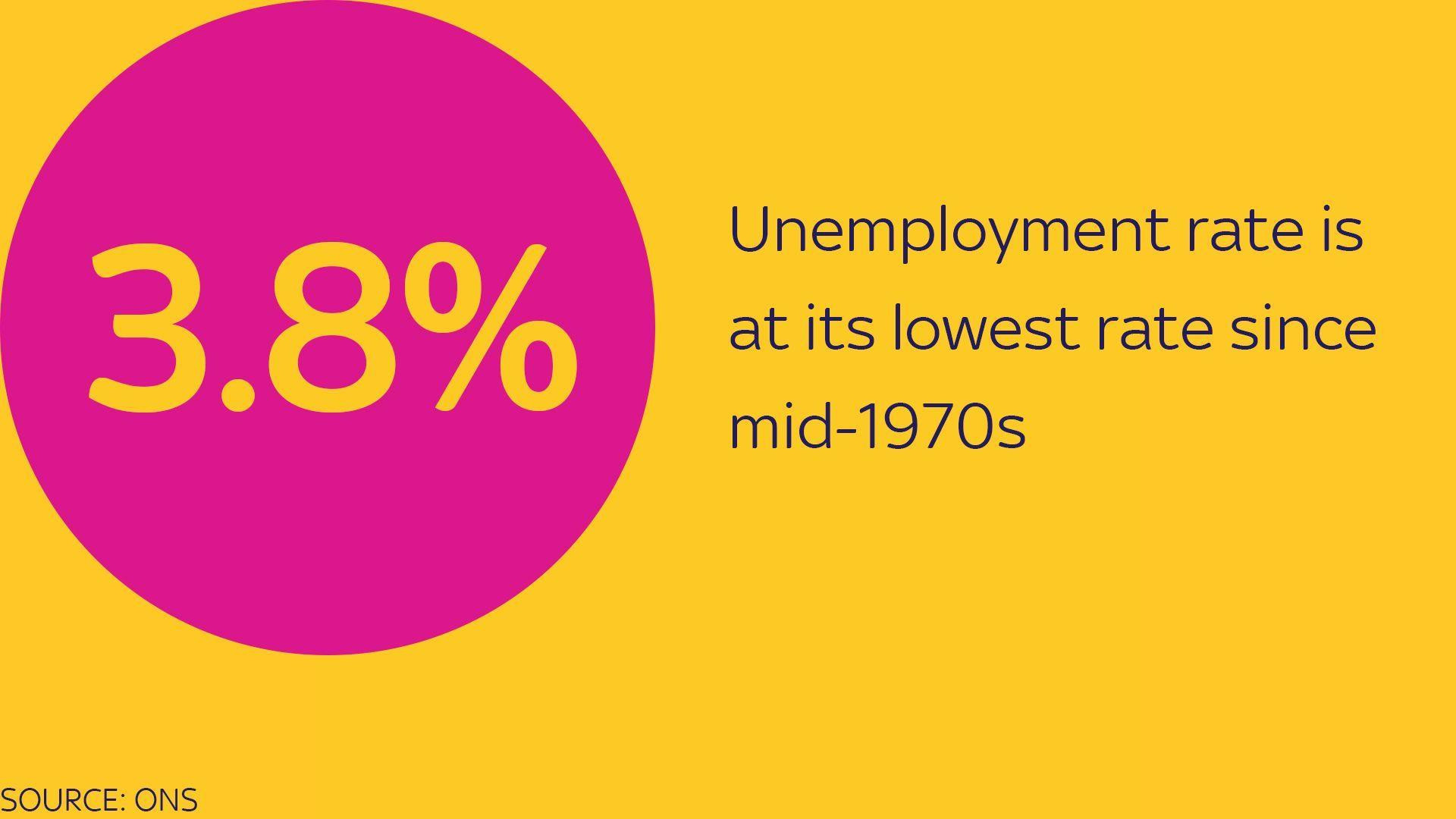

However, the resilience of consumer spending and the labour market show a different picture.

The unemployment rate has been falling for the last six years, and the UK’s employment rate reached a new record high of 76.3%, with most of the growth coming from full-time jobs.

This squeeze on incomes appears to have discouraged household saving, which has slipped below the level of other big economies and is also lower than it has been in the UK for about 20 years.

Theresa May’s time as prime minister came to an end after almost three years (1,106 days) in 10 Downing Street and after delaying Brexit twice.

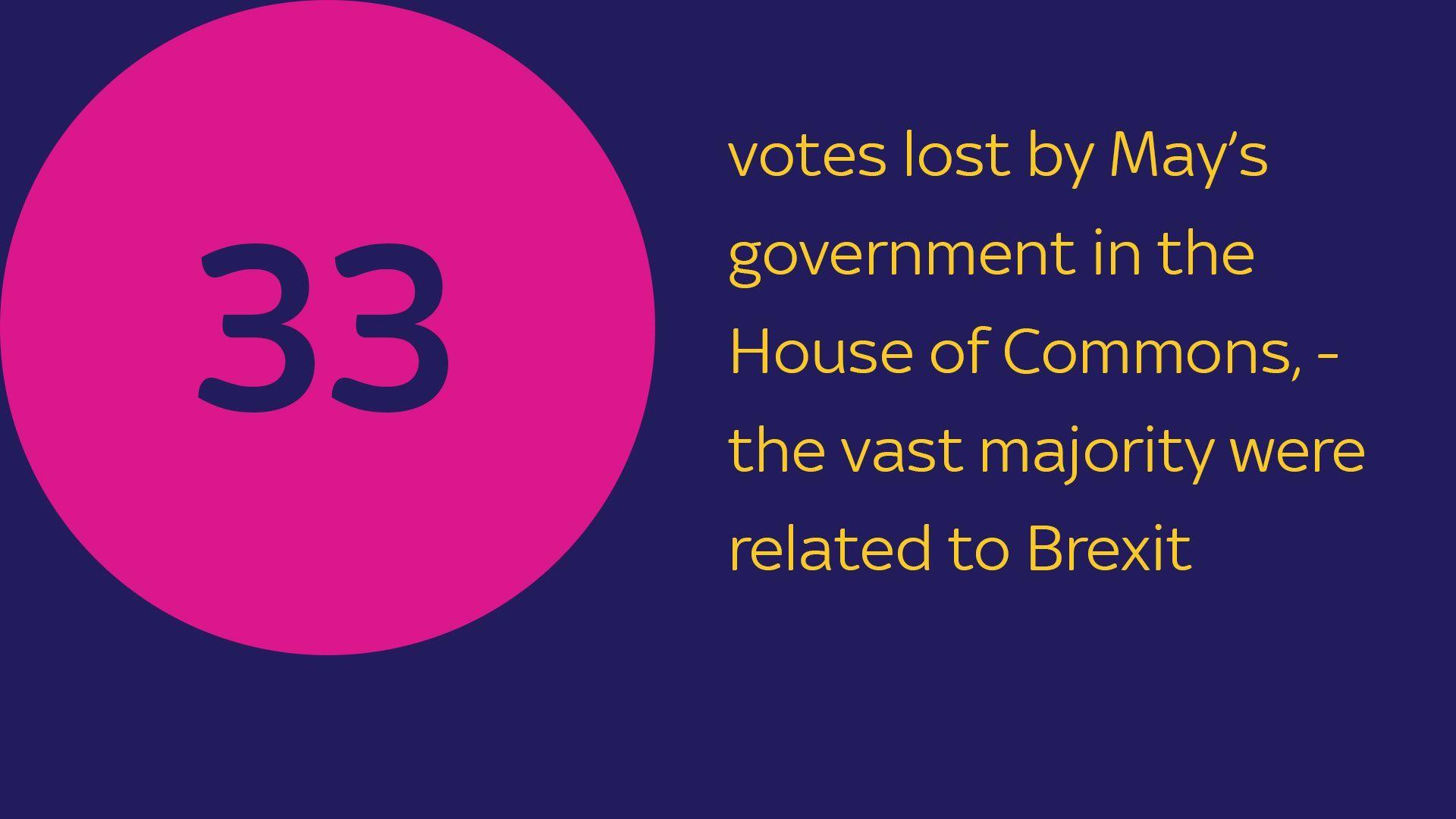

During her time in office she suffered three defeats on her Brexit deal, after a group of Conservative Brexiteer MPs and the DUP – who propped up her government following the 2017 general election – refused to support her withdrawal agreement.

Their concerns centred around the Irish border backstop arrangement, which was an insurance mechanism aimed at avoiding a hard border on the island of Ireland.

The first of Mrs May’s defeats on her Brexit deal was the largest for a sitting government in the history of the House of Commons.

Theresa May’s resignation led to the second general election of the period. As a result, the Conservatives won 365 seats and Boris Johnson continued as PM.

Written and researched: Carmen Aguilar Garcia, Greg Heffer. Graphics: Kalli Ewins-Manolaros, Celt Iwan, Matt Simpson